Does Everyone See Colours The Same?

While it’s commonly understood that people with colourblindness experience colour differently than the average person, did you know research shows that we all see colours differently? The average human eye can detect up to 10 million colours, and our colour perception is based on many biological and cultural factors, like genetics, gender, language, and ethnicity. In this blog post we will break down how and why these elements factor into how we perceive colour!

What biological factors affect colour vision? Genetics, gender, and age

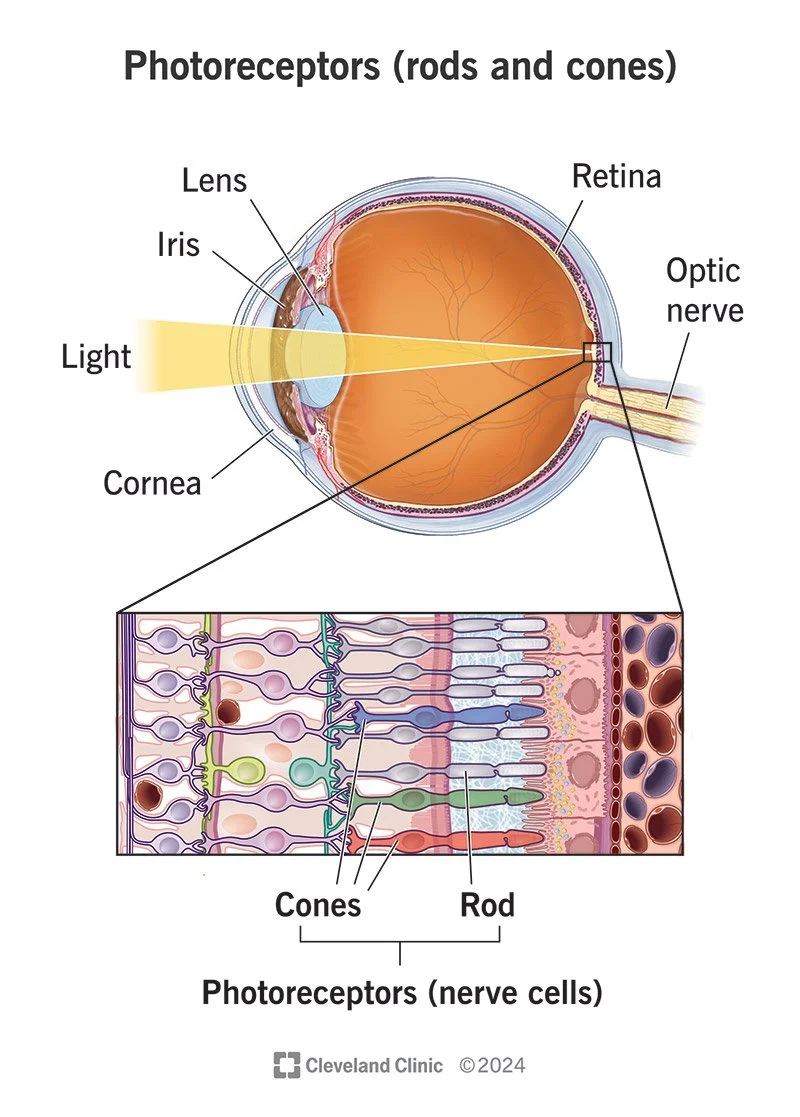

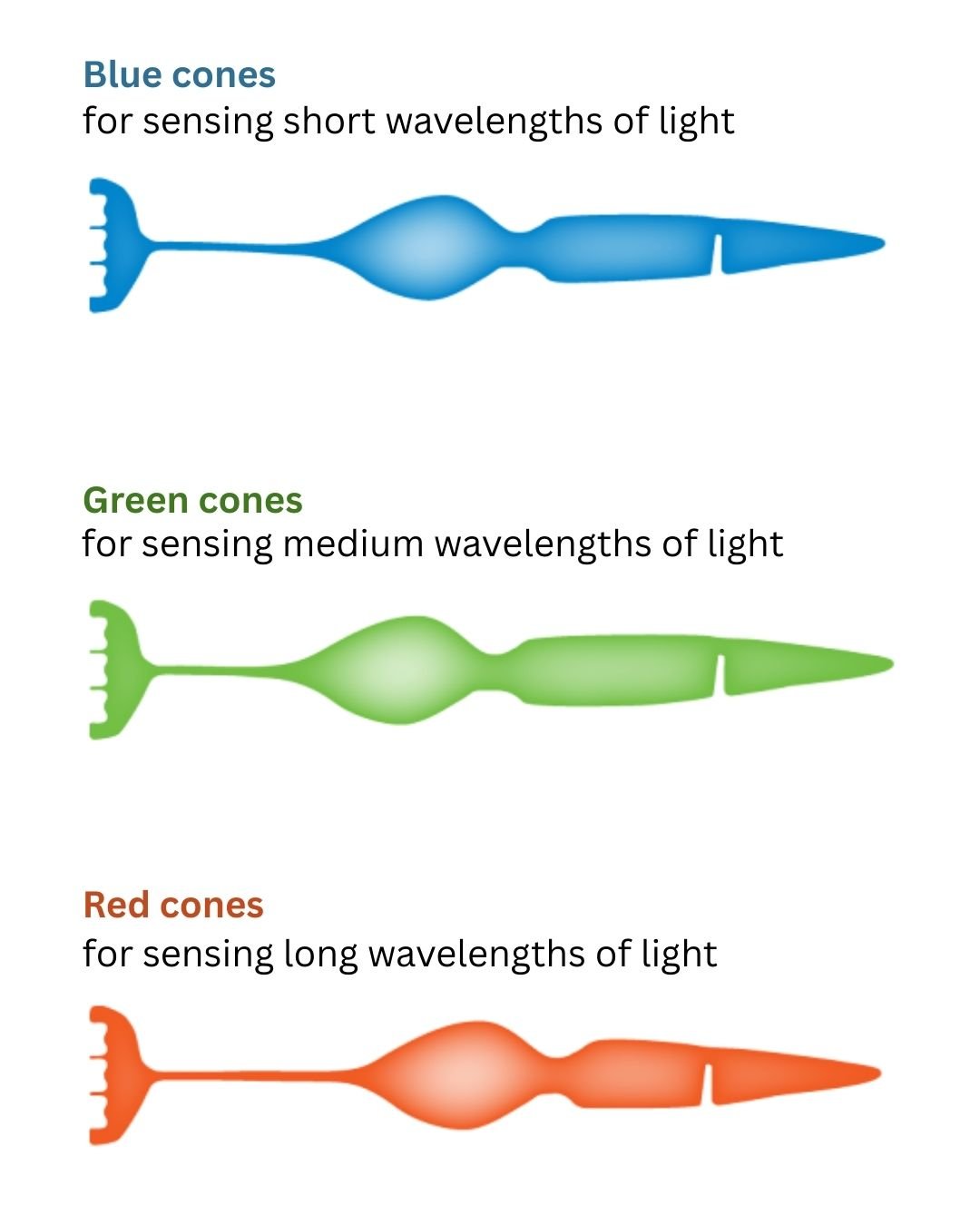

Many genetic conditions such as colour blindness, macular degeneration, and retinitis pigmentosa can affect how we see colour, but even eyes without any conditions see colours uniquely simply from the unique variation of photoreceptors in each of our eyes. Photoreceptors, also known as cones and rods, are responsible for converting the light that our eyes receive into neural signals that our brain can understand. Most people have three types of cones to sense light: blue, green, and red sensing cones which is called trichromacy.

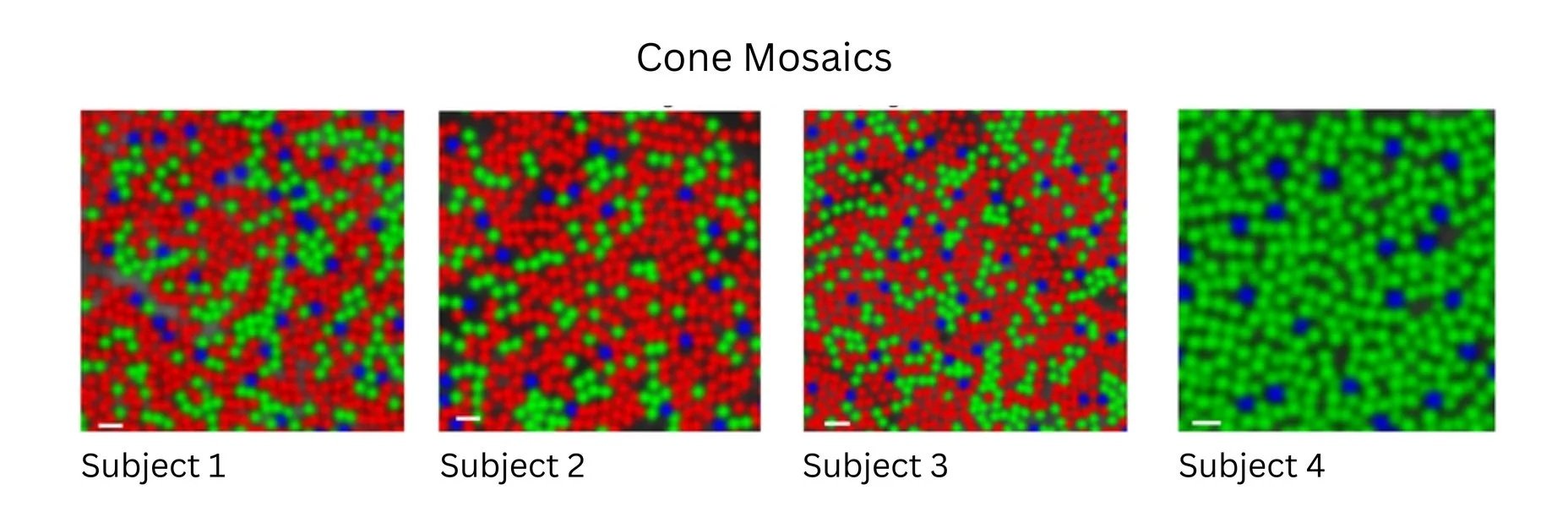

Our cones and rods vary in amounts, density, and distribution from person to person, influencing the way our eyes process colour. You can see this phenomenon in photo below of cone mosaics, which depicts three people with normal colour vision (Subjects 1-3) and the unique ratio of cones they have using adaptive-optics imaging.

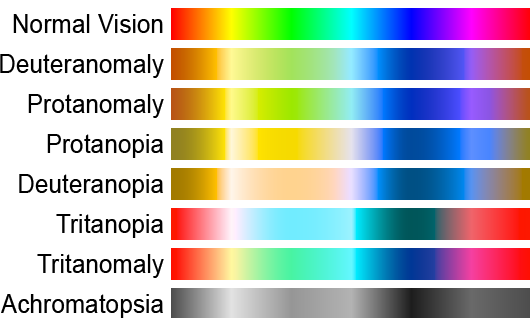

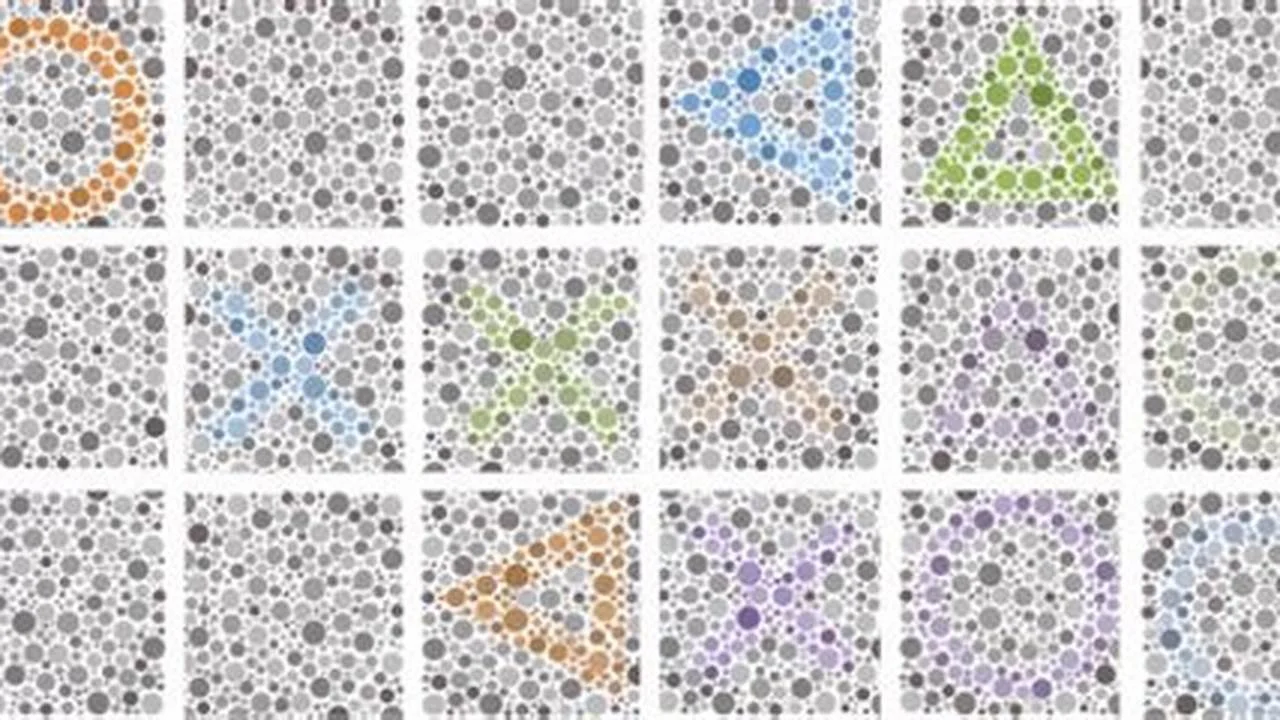

A rare genetic mutation can occur in women called tetrachromacy which means they possess four types of cones instead of three, allowing affected women to decipher up to 100 million colours. On the other hand men are genetically more likely to experience red-green colour blindness, meaning they are lacking sufficient red or green sensing cones as depicted in Subject 4’s cone mosaic image. The chart below shows how our colour perception can vary with different types of colour blindness.

What are the types of colour blindness?

There are seven types of colour blindness:

Deuteranomaly: Individuals have less green cones and can typically see some shades of green, but their green sensitivity is weak. This is the most common type of colourblindness.

Deuteranopia: Individuals lack green cones.

Protanomaly: Individuals have less red cones and can typically see some shades of red, but their red sensitivity is weak. This is the second most common type of colour blindness.

Protanopia: Individuals lack red cones. (Subject 4’s colour blindness type)

Tritanomaly: Individuals have less blue cones and can typically see some shades of blue, but their blue sensitivity is weak

Tritanopia: Individuals lack blue cones.

Achromatopsia (Monochromacy): Individuals lack functional cone cells or only one cone type is functional, leading to no colour vision at all or limited visual acuity. This is extremely rare, affecting around 1 in 30,000 individuals.

What happens to our colour vision as we get older?

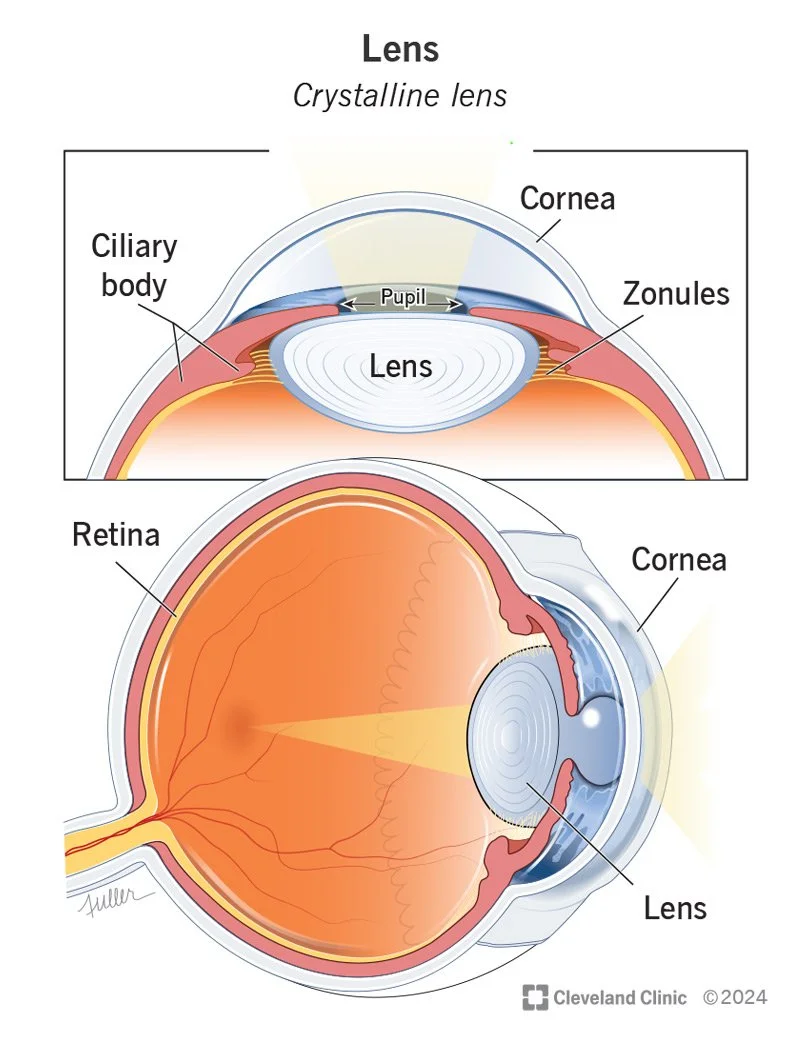

The way we see colour can also change as we get older, due to the natural aging process of our crystalline lens. Located just behind the iris, the crystalline lens focuses light onto our retinas. When we are young this lens is very malleable and changes shape to adjust to see things at various distances. However, as we age the crystalline lens hardens and yellows, reducing its ability to adapt to different conditions. Consequently, colours may appear slightly muted and blues, greens, and purples can become more challenging to distinguish between.

What cultural factors affect colour vision? Language, region, and ethnicity

While the average human eye can detect and differentiate between millions of colours, we tend to categorize them into groups like blue, purple, red, and yellow. Many of us in Canada grew up learning the colours of the rainbow in English with the ROYGBIV acronym, but other cultures and languages define colour groups differently. Some languages have more ways to categorize colour groups whereas others have less; like the Hanunóo people of the Philippines who have four “darkness, lightness, dryness, and wetness”.

While this may seem trivial, research shows that the way we label colours makes a difference in how we perceive them. An extensive or limited vocabulary for colour categorization doesn’t affect the amount of colours we are capable of seeing, but it can affect how easily and quickly we differentiate between shades. For example: Russian has two words for blue; siniy (Синий) for dark blues and goluboy (Голубой) for light blues, categorizing shades of blue into two groups based on intensity and shade. Professor Anna Franklin and her team at the University of Sussex say that this distinction makes Russian speakers more sensitive to recognizing different blues. They were able to test this by “measuring the electrical activity of the brain… in Russian speakers compared to others when they are asked to differentiate between two shades of blue”.

They concluded that colour language may not fundamentally alter the way colours are seen, but it does alter how we think about colour and visualize them cognitively. Additionally, culture can alter how we perceive colour through association. For example, green in western cultures is usually linked to nature, sustainability, money, and emotions like calmness or envy.

Test your colour perception!

As you have learnt, both our brain and our eyes play a role in how we see colour! Many patients do not even realize they have altered colour perception until they are seen by an Optometrist, especially when they are young. Here at View Optometry, the Hardy-Rand-Rittler (HRR) test is one of a few ways our Optometrist assesses colour vision. If you would like to test your own or a loved ones colour perception, please schedule a visit with us by calling 604 770 2095 or by booking online!